Helping Kids Read Their Anxiety Signals

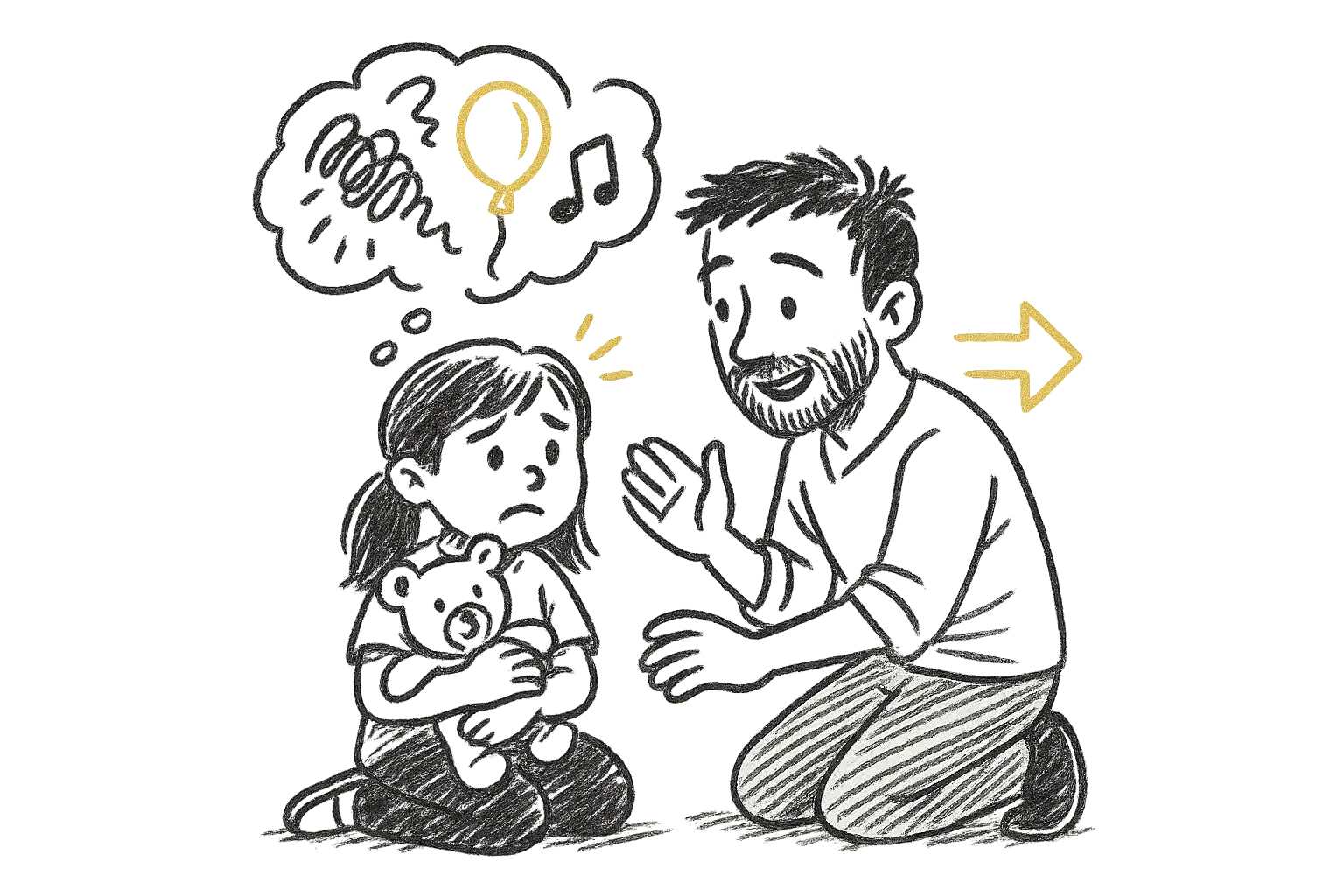

Right before we left for a friend’s birthday party, my daughter told me she was feeling anxious. She wasn’t quite sure why, but as we talked it through, she figured it out: “I’m nervous because the birthday boy isn’t in my class. What if I don’t have any friends there?”

I told her that was normal. Even adults feel that way — especially the parents who walk into kids’ parties not knowing the other parents. That seemed to help a little.

She admitted that’s why she sometimes brings a plushie with her. It makes her feel more secure. And she told me about a song she likes — Anxiety by Doechii. She knows the context of the song is a bit different, but one lyric in particular sticks with her: “My anxiety, can’t shake it off of me.” For her, those words capture exactly how it feels in the moment.

On the way there, I reframed the feeling for her. I said anxiety can actually be useful — it energizes your body and mind to get you ready. She surprised me by giving an example herself: “Like on a driver’s test?” I told her that was perfect. It’s the same for school tests, or anything where the nerves push you to focus.

Then I gave her a challenge: “Anxiety doesn’t last forever. Notice when it goes away.”

As we pulled into the neighborhood, she saw a sign that said Follow the balloons to the party. A minute later, she spotted a group of girls walking and realized she knew one of them. They pointed us toward the party.

“See?” I said. “You already know someone here. And that anxious feeling — is it still here?”

She smiled and admitted it was gone. Within ten minutes of arriving, her plushie was left on the table with me.

Why This Worked

Looking back, I realized that in that short car ride we touched on almost every evidence-based strategy for helping kids with anxiety:

- Labeling and normalization. Just calling it “anxiety” made the feeling less mysterious. Research shows naming emotions helps children understand they are temporary, not permanent traits (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006).

- Comfort tools. Her plushie wasn’t a crutch; it was a transitional object — something research shows helps kids handle new or stressful settings by offering steady reassurance (Winnicott, 1953; Passman, 1987).

- Music as regulation. That Doechii lyric gave her a way to put words to what she felt. Studies find kids often use music to regulate mood and cope with stress (Saarikallio, 2011).

- Reframing anxiety as useful. I told her it was her body’s way of gearing up. This reflects the Yerkes-Dodson law: moderate anxiety can actually boost performance (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908).

- Exposure. She still went to the party, even with nerves. Repeatedly facing fears is how anxiety loses its grip (Ollendick & Davis, 2004).

- Mindful noticing. Asking her to notice when anxiety disappeared turned it into an experiment. She experienced firsthand that anxiety rises and falls.

Age Makes a Difference

The tools I used with my daughter work well for her age — she’s school-age, old enough to name feelings, use metaphors, and reflect afterward. But the approach shifts depending on where a child is developmentally:

- Toddlers & Preschoolers (3–6). Focus on reassurance and comfort. Transitional objects (plushies, blankets) are especially powerful here. Instead of reframing anxiety as “helpful energy,” it may be enough to say, “You’re safe, I’m here.”

- School-age Kids (7–10). This is the sweet spot for tools like labeling anxiety, reframing it as energy, and playful challenges (like “notice when it goes away”). Metaphors and concrete examples (tests, performances) resonate at this age.

- Tweens & Teens (11+). Older kids may resist plushies but lean heavily on music, journaling, or peer conversations. Framing anxiety in terms of performance — sports, school tests, auditions — often clicks. They can also start to learn breathing techniques or mindfulness exercises.

Closing Reflection

What struck me is how much she already knew. She had a plushie ready, a lyric that said what she couldn’t, and an intuitive sense that anxiety shows up in important moments.

My role wasn’t to erase the anxiety. It was to give her words, perspective, and reassurance that it’s normal — and temporary.

Because the goal isn’t a life without anxiety. It’s helping kids see it for what it is: a signal, not a stop sign.

References

- Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual. Ardmore: Workbook Publishing.

- Ollendick, T. H., & Davis, T. E. (2004). Empirically supported treatments for children and adolescents with phobic and anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(3), 557–561.

- Passman, R. H. (1987). Preschoolers’ use of a security blanket in home and laboratory. Child Development, 58(3), 853–859.

- Saarikallio, S. (2011). Music as emotional self-regulation throughout adulthood. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 307–327.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 34, 89–97.

- Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18(5), 459–482.

Member discussion