Trails, Ruts, and the Work of Keeping a Brain Flexible

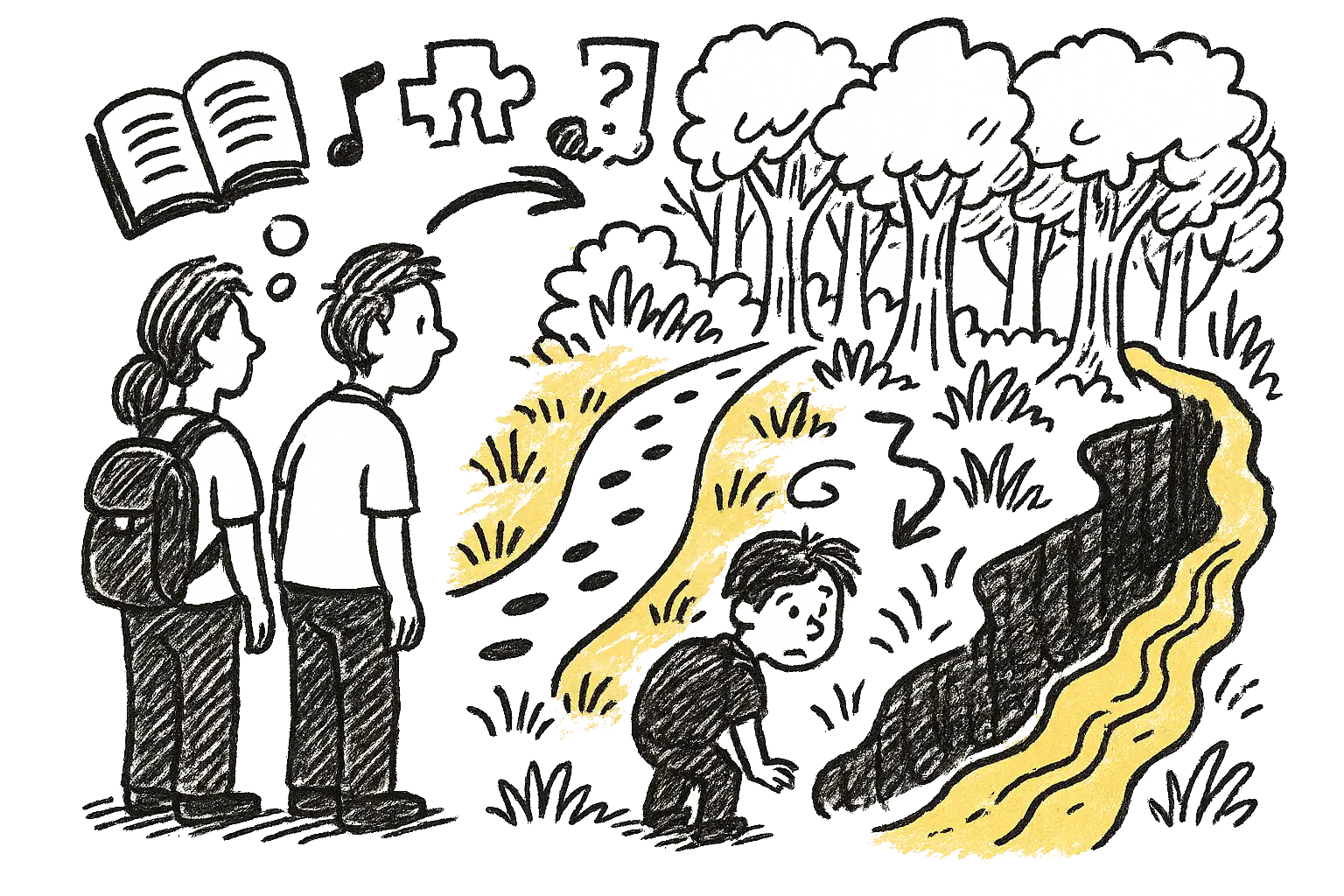

Every fall, I notice it in myself and in my daughter: school starts, and reading feels harder than it did in June. It’s not that we forgot how to read—it’s that the trail grew over while we weren’t walking it.

Neuroscientists have a term for this: synaptic pruning. In the brain, neurons that fire together wire together. Neurons that stop firing? Those pathways weaken and sometimes get trimmed away. It’s the brain’s version of forest management—cutting back to keep things efficient.

The trouble is, efficiency can be a double-edged sword.

Upkeep: Why Skills Slip Without Practice

Teachers call it “summer learning loss.” Research by Kuhfeld & Tarasawa (2020) found that kids lose between 17% and 34% of their previous year’s learning over summer break, especially in math. When the trail isn’t used, the brush creeps back.

You feel it in your head, too: the networks for reading—the occipito-temporal cortex (recognizing words) and the angular gyrus (making meaning)—start to feel rusty when they’ve been idle. Picking up a book in September feels harder because the brain is literally re-clearing the path.

Pruning: The Cost of Letting Go

Pruning isn’t a flaw; it’s how children refine motor skills, language, and problem-solving. But it’s not always neutral. If a skill or language isn’t reinforced, the brain reallocates those resources.

Research on second language acquisition suggests there may be a “critical period” where younger learners have a distinct advantage, often retaining more native-like fluency. A large-scale study by Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, & Pinker (2018) showed that ease of learning declines steeply after puberty, though scientists debate exactly when the window begins to narrow—some argue as early as age 7, others closer to adolescence. A few adults do manage near-native fluency, but they’re the exceptions, not the rule.

Think of a child who stops piano at ten. The path through that part of the forest starts to fade. Years later, returning feels like hacking through weeds, not striding down a trail.

Ruts: When Strong Trails Turn Against You

Here’s the part I didn’t need a journal article to tell me: sometimes a trail becomes so deep it turns into a rut. I’ve had thought patterns—self-doubt, anxious predictions—that felt impossible to climb out of.

Neuroscience explains why. Reinforced circuits in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex can trap the brain in loops of negative emotion. Disner et al. (2011) showed how these rigid trails contribute to depression: the brain keeps firing the same path, even when it leads nowhere good. The same mechanism that makes us fluent in reading or biking can also make us fluent in self-criticism.

Neuroplasticity isn’t automatically good. A well-worn path can be a skill—or a prison.

Keeping the Forest Alive

So how do we keep the brain’s forest from turning into overgrowth on one side and ruts on the other? Neuroscience offers a few strategies:

- Upkeep: Small, regular practice keeps trails clear. Spaced repetition—reviewing information at gradually increasing intervals—boosts long-term retention far more than cramming (Cepeda et al., 2006).

- Prune wisely: Mistakes are essential. Each error helps the brain cut back inefficient routes and replace them with stronger ones.

- Prevent ruts: Variety matters. Reading fiction and nonfiction, playing music, solving problems in new ways—each builds cognitive flexibility. Mindfulness, too, appears to strengthen new pathways while quieting rigid stress circuits (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

I think about this when I catch myself sliding into old grooves. Psychologists call this cognitive reappraisal—deliberately reframing a thought or situation in a more constructive way. For example, shifting “I’m going to fail this test” into “This test is hard, but I’ve prepared as best I can.” Each reframe helps weaken the old rut and carve a fresher trail. For me, it feels like bushwhacking through tangled brush to make a new path, while the old one still whispers for me to come back.

Walking Together

That’s the paradox of our brains: they’re designed for efficiency, but efficiency without flexibility becomes fragility.

When my daughter sits down with a book in September and sighs, “This feels harder,” I remind her: the trail isn’t gone. We just need to walk it again. And when I catch myself rehearsing the same anxious thought for the hundredth time, I try to take my own advice—step off the rut, wander into the brush, and make a new way through.

Because the real work—whether we’re talking about kids learning to read or adults unlearning patterns of fear—is to keep the right trails open, trim back the ones that don’t serve us, and wander often enough that the forest stays alive.

References

- Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380.

- Disner, S. G., Beevers, C. G., Haigh, E. A., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(8), 467–477.

- Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition, 177, 263–277.

- Kuhfeld, M., & Tarasawa, B. (2020). The COVID-19 slide: What summer learning loss can tell us about the potential impact of school closures on student academic achievement. Brookings.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225.

Member discussion