When a Childhood Friendship Stops Fitting

My daughter has grown up with the boy next door. They’ve been friends since before she could even ride a bike, and for years their age gap didn’t seem to matter. At five and nine, they were both still kids chasing each other around the yard.

Now, she’s in third grade and he’s in seventh. And suddenly, I’m the only one who seems to notice the shift.

Everyone else just sees “kids playing.” I see the red flags.

Why the Gap Matters

On paper, four years doesn’t sound like much. But in child development terms, the difference between eight and twelve can be enormous.

Third graders (ages 8–9) are still in what Piaget called the concrete operational stage. They play for fun, fairness, and belonging. Seventh graders (12–13) are entering early adolescence: testing independence, wrestling with identity, and increasingly shaped by peers (Brown & Larson, 2009).

That’s why schools don’t mix these grades at recess. What’s playful for an 8-year-old can be power play for a 12-year-old.

What I Saw

The differences weren’t theoretical. They showed up in my yard, in ways too subtle for kids to articulate but too clear for me to miss.

- The hammock. My daughter and a younger neighbor would climb in together, giggling. Then the seventh grader would plop himself in the center, leaving no room for the littler kids. Was it dominance? Maybe. Or maybe it was just normal “I want the middle” behavior. Either way, the younger ones ended up squeezed out.

One time, while all three were crammed together, my daughter called out: “Hey, that’s my suss spot!” He brushed it off as an accident and told her she was making it awkward. Not malicious, but a glimpse of the maturity gap — he had the verbal upper hand, reframing blame in ways a younger child can’t yet counter.

On another occasion, the younger boy neighbor made his own exaggerated claim — saying the older boy’s hand was “in his butthole.” Likely hyperbolic, but it told me something important: these “accidents” may not be isolated.

Based on child safety literature (Finkelhor, 2009; Wurtele & Kenny, 2010; NSPCC, 2016), my understanding is that while a single accidental bump or touch may not be concerning, a pattern of repeated “accidental” contact — especially when followed by dismissing or blaming a younger child — should be treated as a red flag. The research highlights that boundary-testing behaviors, minimization, and lack of accountability are risk factors in unsafe dynamics. This doesn’t prove bad intent, but it does indicate that the situation may be unsafe without clearer boundaries and adult oversight.

That’s when I stepped in. I set a new rule: the hammock was for two at a time, they’d take turns, and when I wasn’t around, my daughter was in charge of it — not the older boy. Later, I talked with her privately. I told her accidents do happen, but not often. If it keeps happening, it’s “suss.” I used myself as the example: “Have I ever accidentally touched your suss spot? No. It can happen once, but it shouldn’t happen again and again.” - Age-inappropriate play. The older boy once introduced them to a game he called Abusive Dad, based on a video game he’d been playing. In their version, he played the “drunk dad,” yelling at the younger kids as if they were his children. Around the same time, my daughter learned what a prostitute was — not because she asked, but because the older kids had overheard adults and repeated it. At least they reassured another parent: “Don’t worry, we won’t talk about cocaine or cigarettes around your daughter.” As if that was the bar.

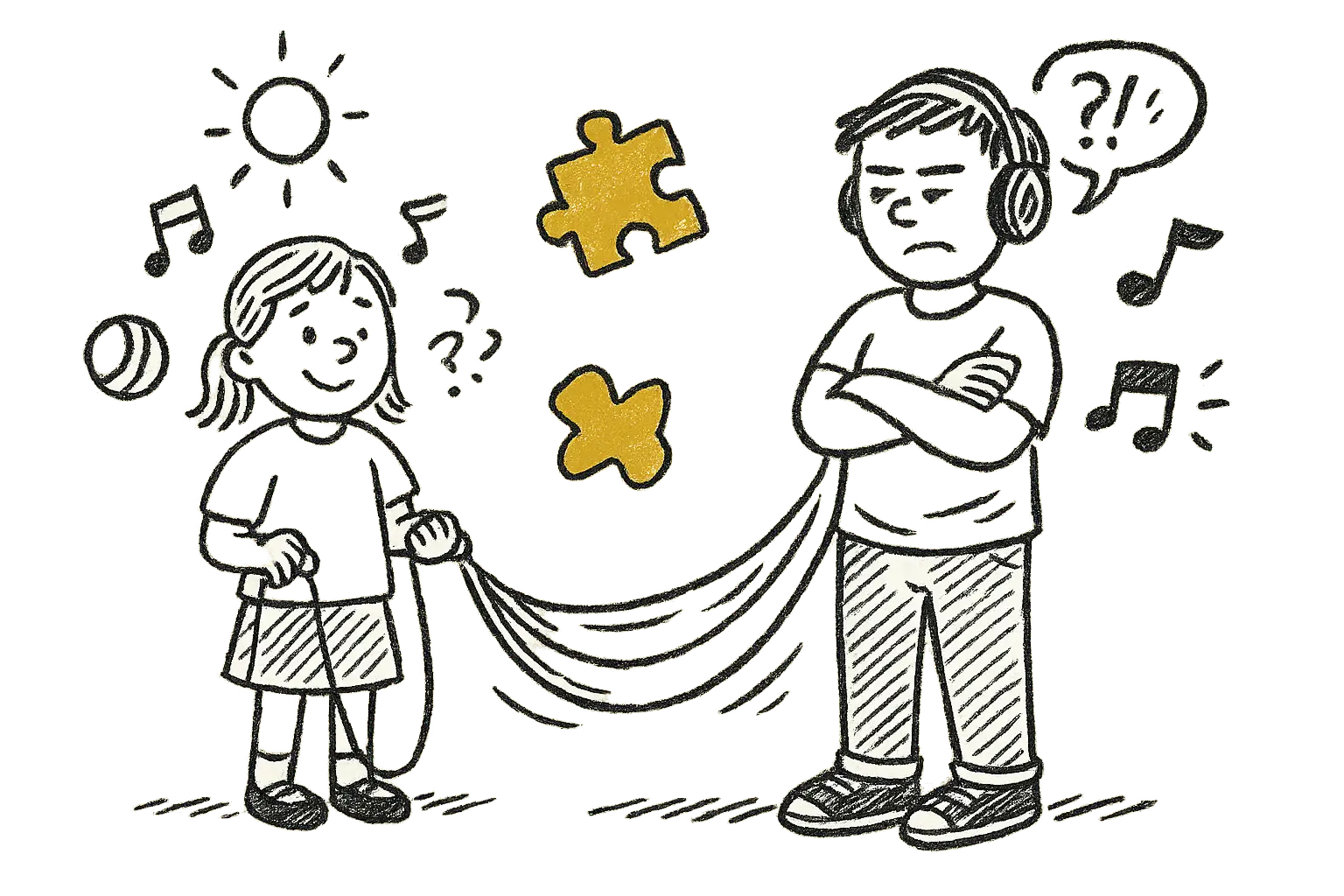

Research shows that early exposure to adult content — whether through games, overheard conversations, or peers — can confuse kids or normalize behaviors long before they’re developmentally ready (Martino et al., 2006). For children in middle childhood, play is usually about fun and imagination, not rehearsing adult conflicts. So when the play themes shifted toward substance abuse and exploitation, it wasn’t just edgy pretend play — it was a developmental mismatch with potential to distort how the younger ones understood relationships. - Different media worlds. My daughter loves silly meme songs she can sing along to. He likes dark rap that glorifies violence. Developmentally, that makes sense: younger kids are drawn to rhythm and repetition, while adolescents use music to explore identity and rebellion (North & Hargreaves, 2008). But side-by-side, those worlds clash.

When Cross-Age Friendships Work

To be fair, not every awkward moment signals danger. Kids wrestle, claim spots, stumble into each other, and sometimes play with taboo ideas. Psychologists note that children often flirt with “forbidden” themes in safe contexts, and most of the time it doesn’t leave lasting harm (Gray, 2011).

Cross-age friendships can also be valuable. Younger kids can gain confidence, while older kids practice empathy and leadership. In many cultures, age-mixed play is the norm, not the exception — siblings, cousins, and neighbors all mixing together under the watchful eye of community. Even here, structured groups like scouting or sports often blend ages successfully.

And development itself varies. Puberty can begin as early as 8 in girls and 9 in boys, or as late as 13–14. Some twelve-year-olds are still childlike; some eight-year-olds seem far ahead of their years. The “gap” doesn’t look identical in every friendship.

Why My Concerns Still Stood

In our case, though, the patterns leaned the other way. The hammock squeezes, the awkward “accidents,” the edgy games, the media mismatch — each on its own could be explained away, but together they formed a repeated pattern of discomfort and dismissal. That’s when child safety literature says parents should step in.

Developmental psychology backs this up: friendships in middle childhood are about companionship, while early adolescent friendships are about identity and social comparison (Buhrmester, 1990). That mismatch can leave the younger child sidelined, pressured, or repeatedly exposed to situations they don’t fully understand.

The Parenting Dilemma

I could have banned the friendship outright. But that risked teaching her that noticing problems means she loses people she cares about.

Instead, I tried to walk the harder middle:

- Supervise and set limits. Play outside, in groups, not behind closed doors.

- Affirm her instincts. When she said something felt wrong, I told her she was right to notice. Trusting her gut is a skill I want her to keep.

- Broaden her circle. I nudged her toward classmates, so she has friendships that match her stage.

- Talk openly. I explained that people change as they grow, and sometimes friends drift apart. That doesn’t erase the good memories.

Helping kids through these transitions matters. Research shows children who understand that friendships naturally shift over time cope better with the feelings of loss or rejection (Rose & Asher, 2004).

Closing Reflection

The hardest part of parenting is being the one who notices when something doesn’t fit anymore. My daughter didn’t see the power imbalance. Other adults brushed it off. But I saw it — the subtle shift from innocent play to lopsided influence, with patterns that child safety experts tell us to take seriously.

Maybe that’s our role: to be the watchful ones, stepping in when “normal” play carries too much weight for a child to hold.

I don’t want her to lose the sweetness of that neighbor friendship. I just want her to carry forward the laughter, the bike rides, the kindness — without carrying the weight of things she isn’t ready for.

Because childhood friendships are precious. But not every friendship is meant to last every stage.

References

- Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., Fishbein, M., & Jordan, A. (2008). It works both ways: The relationship between exposure to sexual media content and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology, 11(4), 443–461.

- Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 2, 74–103.

- Bukowski, W. M., Laursen, B., & Rubin, K. H. (2018). Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. Guilford Press.

- Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61(4), 1101–1111.

- Finkelhor, D. (2009). The Prevention of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Future of Children, 19(2), 169–194.

- Gray, P. (2011). The special value of children’s age-mixed play. American Journal of Play, 3(4), 500–522.

- Martino, S. C., Collins, R. L., Elliott, M. N., Strachman, A., Kanouse, D. E., & Berry, S. H. (2006). Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics, 118(2), e430–e441.

- North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2008). The social and applied psychology of music. Oxford University Press.

- Recchia, H. E., & Howe, N. (2009). Family talk about internal states and children’s relative appraisals of self and sibling. Child Development, 80(3), 951–961.

- Rose, A. J., & Asher, S. R. (2004). Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Development, 75(3), 749–763.

Member discussion